What It (Actually) Takes to Land Your First Job in 2025

New data from thousands of students reveals the hidden costs of getting hired: 135 hours, 78 applications, and hundreds to thousands of dollars spent, with major disparities by field, race, and school. Plus, the helpfulness of career centers and what students are doing to increase their chances.

Posted October 25, 2025

Table of Contents

In today’s job market, getting hired after college is no longer a victory lap at the end of a four-year sprint. It’s a marathon of unpaid work, escalating expenses, and mounting frustration, made all the more grueling by the sense that colleges and universities are falling short when students need them most.

This isn’t anecdotal. We recently surveyed thousands of students and recent graduates across every major, type of school, and career path in America, and the numbers paint a stark, data-driven portrait of an imperfect, often broken system and a generation forced to hustle harder than ever just to reach the starting line.

The Real Price of Getting Hired

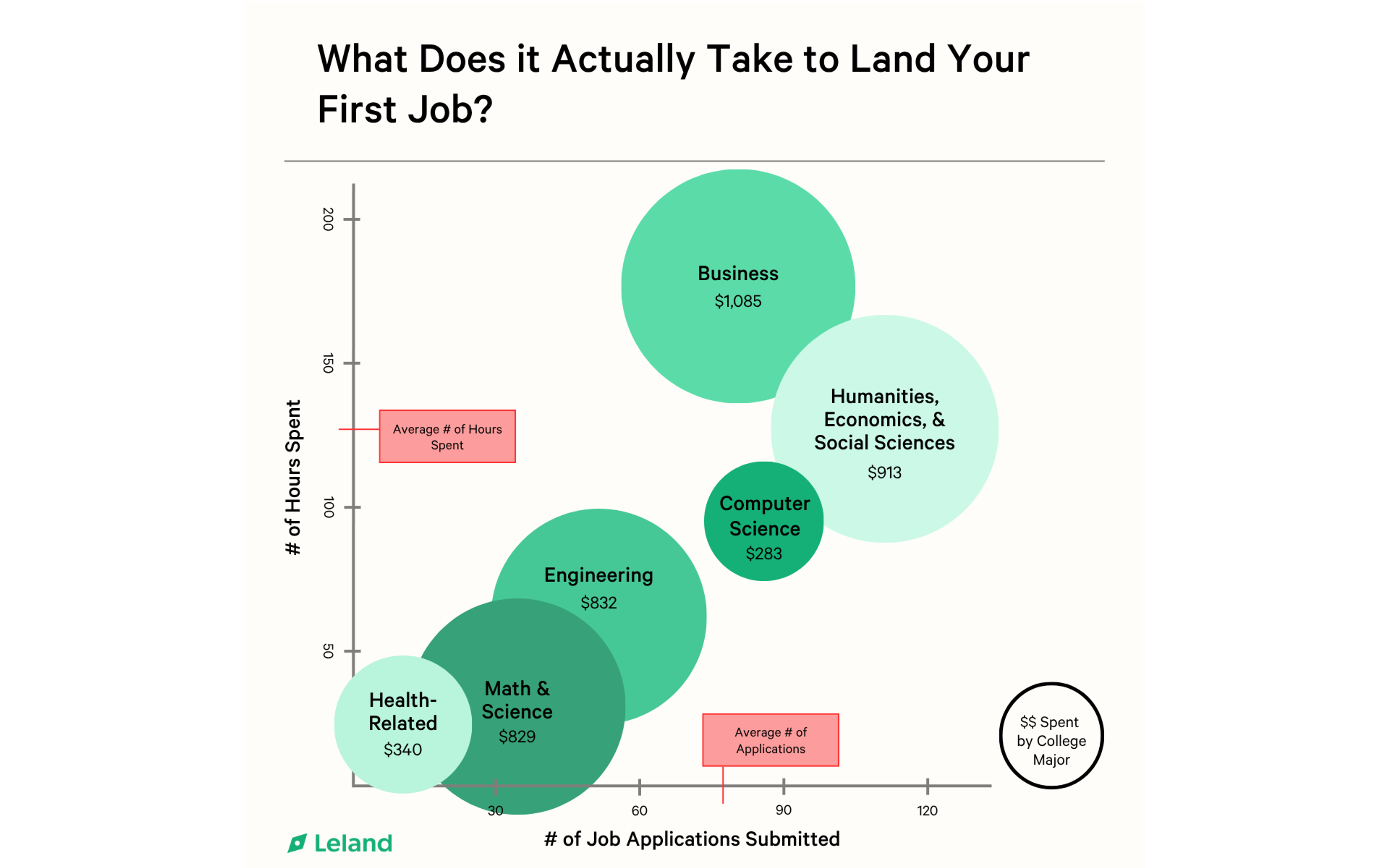

How Much it Costs & How Many Applications it Takes to Get a Job

For today’s college students, landing that coveted first job is less of a milestone and more of a second job. It’s one that demands time, money, and grit, and has no guarantee of return. According to this new data, the average graduate spends 135 hours and submits 78 applications just to secure a single offer.

But these averages mask deep differences in students by major, gender, race, target industry, and more.

Students majoring in computer science report the lowest financial cost of entry, $283 on average, but still face an uphill climb. They submit around 88 applications and spend 90 hours on the job hunt. That’s not just a job search; it’s a semester-long grind happening on top of finals, classes, internships, and life.

Engineering majors aren’t far behind in terms of time and effort. They spend 65 hours and apply to 54 jobs, all while shelling out $832 to land their first role.

Business majors carry the heaviest time burden of any field. On average, they invest 175 hours and submit 76 applications – nearly double the average job-search hours across all majors – and spend an average of $1085, the most of any major.

Meanwhile, humanities, economics, and social science majors, often stereotyped as “less employable”, aren’t coasting either. They apply to the most jobs of any group (113 on average) and spend 132 hours to land a role, while shouldering $913 in costs.

The two outliers? Math and science majors spend $829, apply to just 38 jobs, and clock 32 hours on the search. Health-related majors like nursing, public health, and pre-dentistry report the lowest burden overall, spending just $340, submitting 11 applications, and putting in 20 hours. That likely reflects the strong and growing demand for healthcare workers in the broader economy.

The takeaway here is clear: without institutional bridges or structured entry points, the cost of ambition falls squarely on students’ shoulders. And for many, breaking into their chosen field now requires the kind of labor, strategy, and sacrifice once reserved for the job itself. A college degree is no longer a guarantee of employment and opportunities are not distributed equally.

So Much Work, Students Are Delaying Graduation

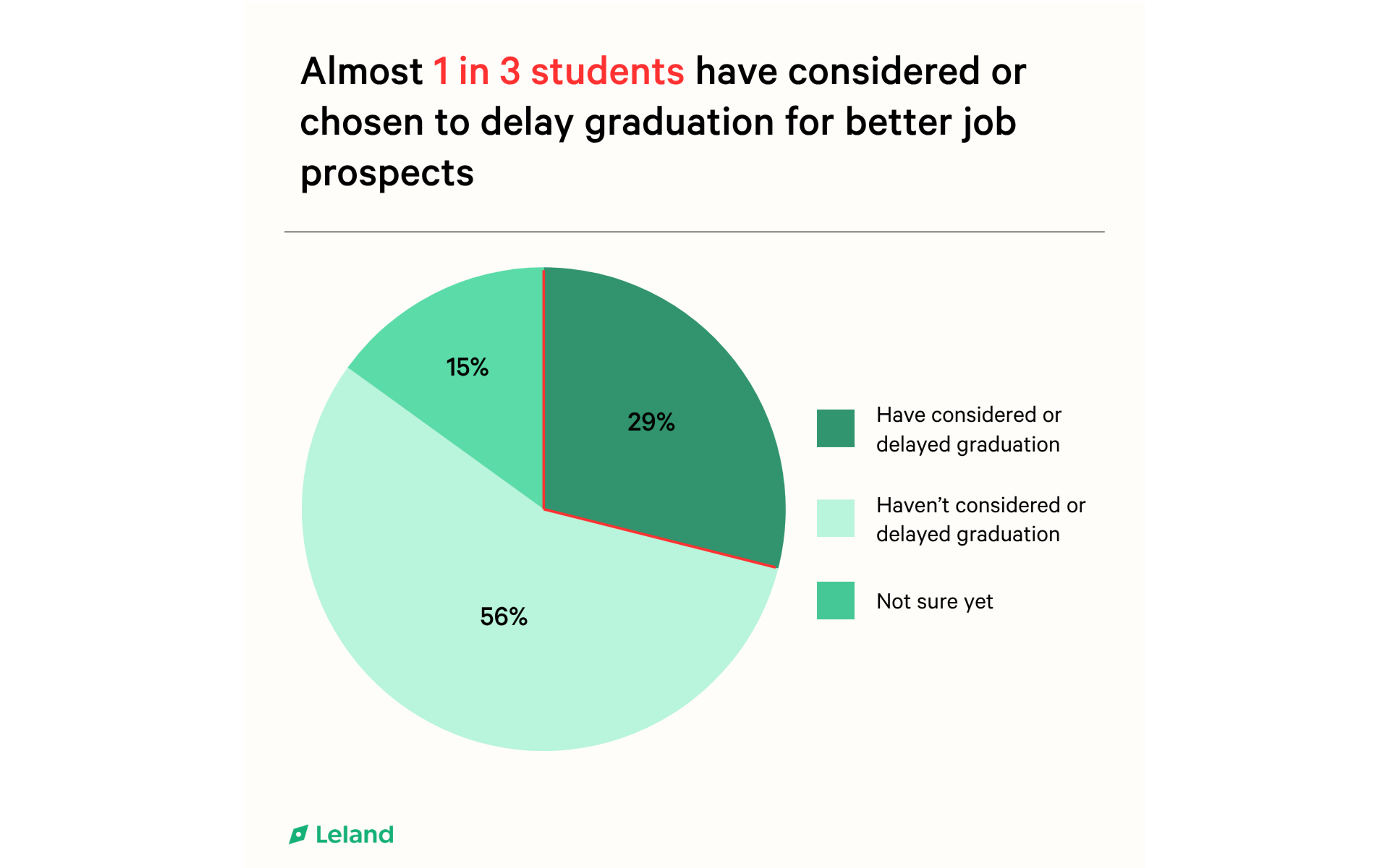

So, what happens in a system where effort doesn’t always lead to outcomes? Students begin to buy time. Faced with the mounting pressure of the job hunt, we found that nearly 1 in 3 students have either delayed graduation or seriously considered it – not to finish coursework, but to improve their job prospects.

This isn't a fringe phenomenon. The survey data shows a quiet, structural shift: graduation is becoming negotiable. And, it’s disproportionately affecting certain groups.

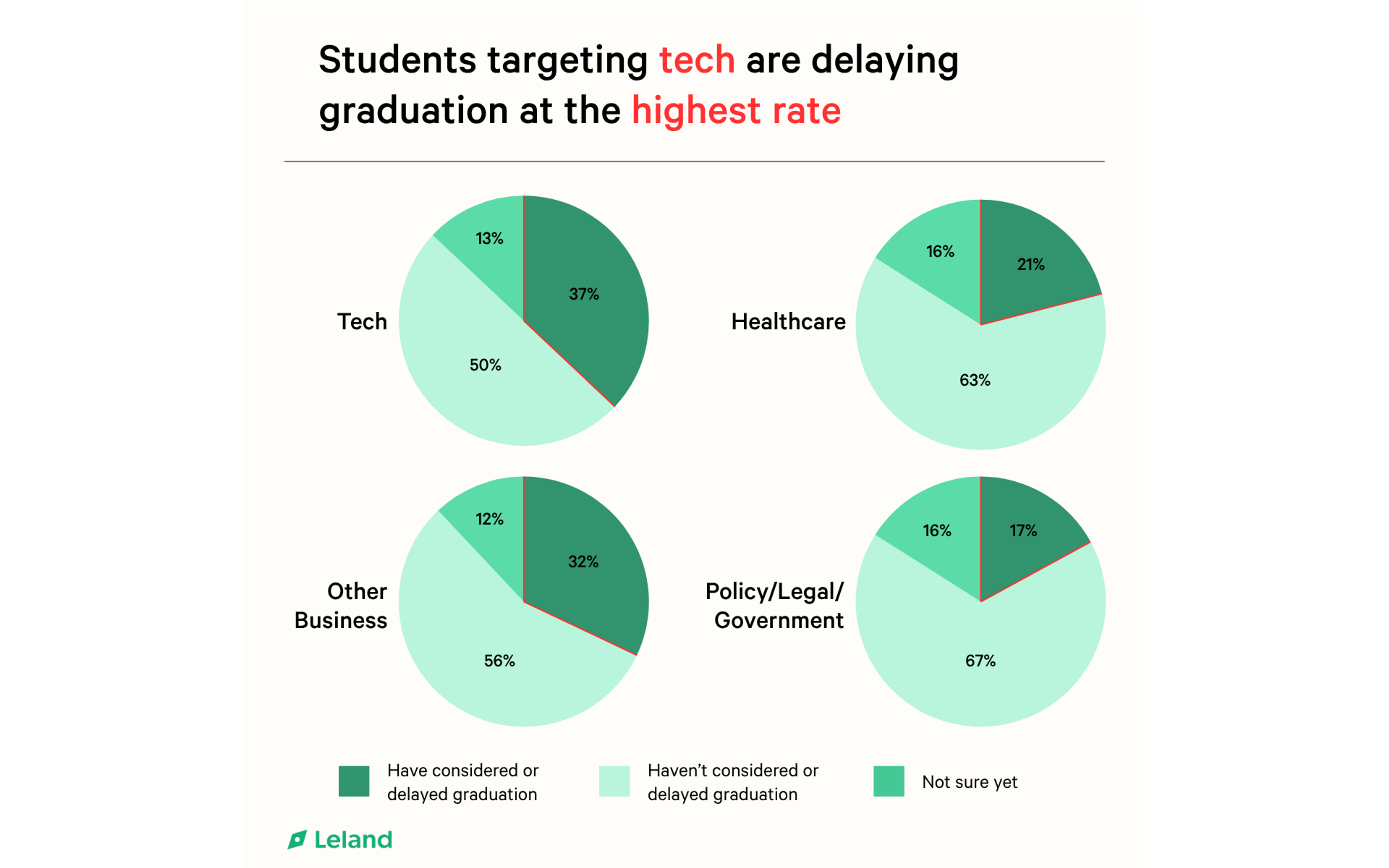

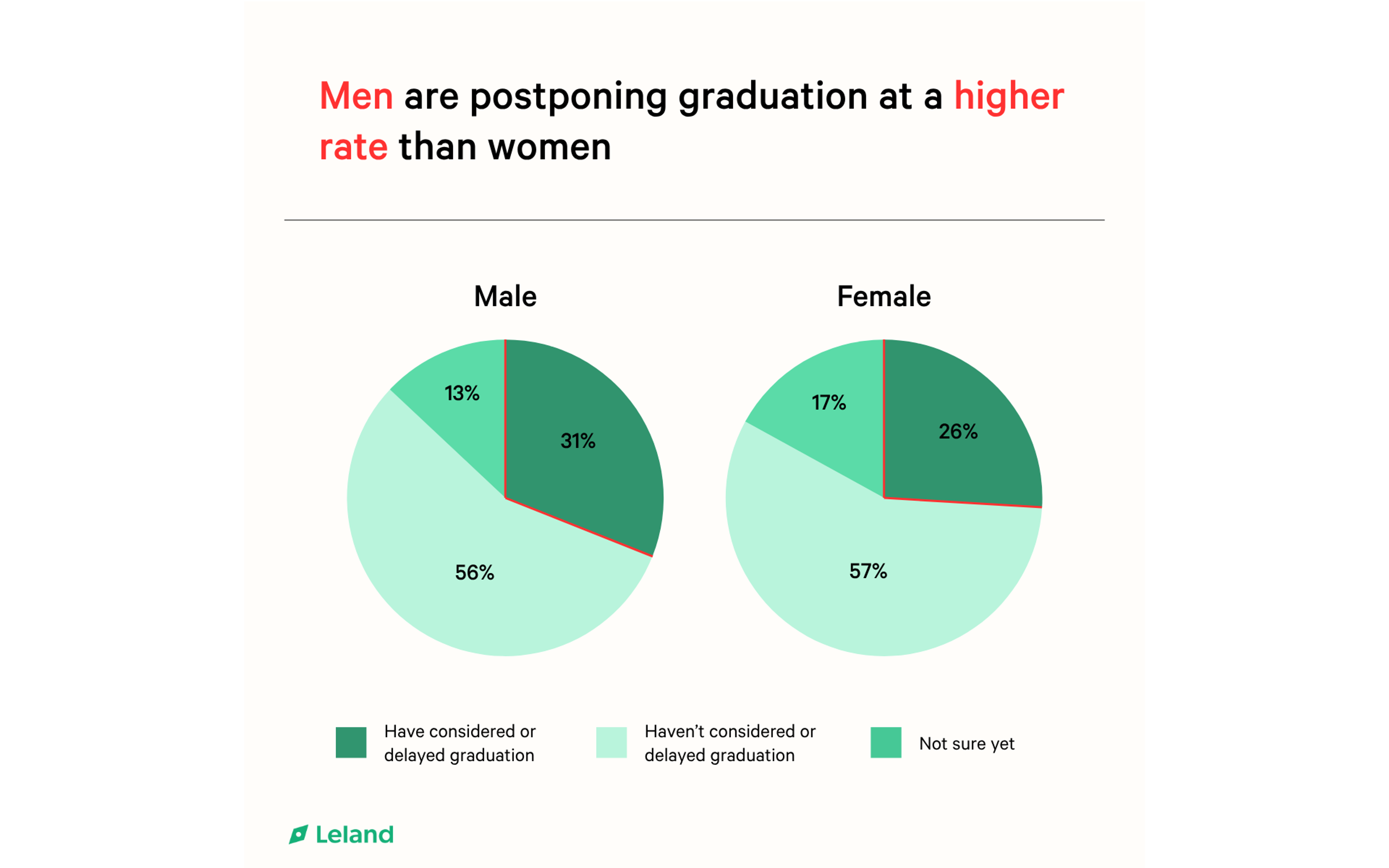

Men are more likely than women to postpone graduation, with 31% reporting they’ve considered or already delayed, compared to 26% of women. The trend also skews by industry: tech-bound students lead the way, with a striking 37% opting to delay, far higher than their peers in healthcare (21%), business (32%), and policy/government (17%).

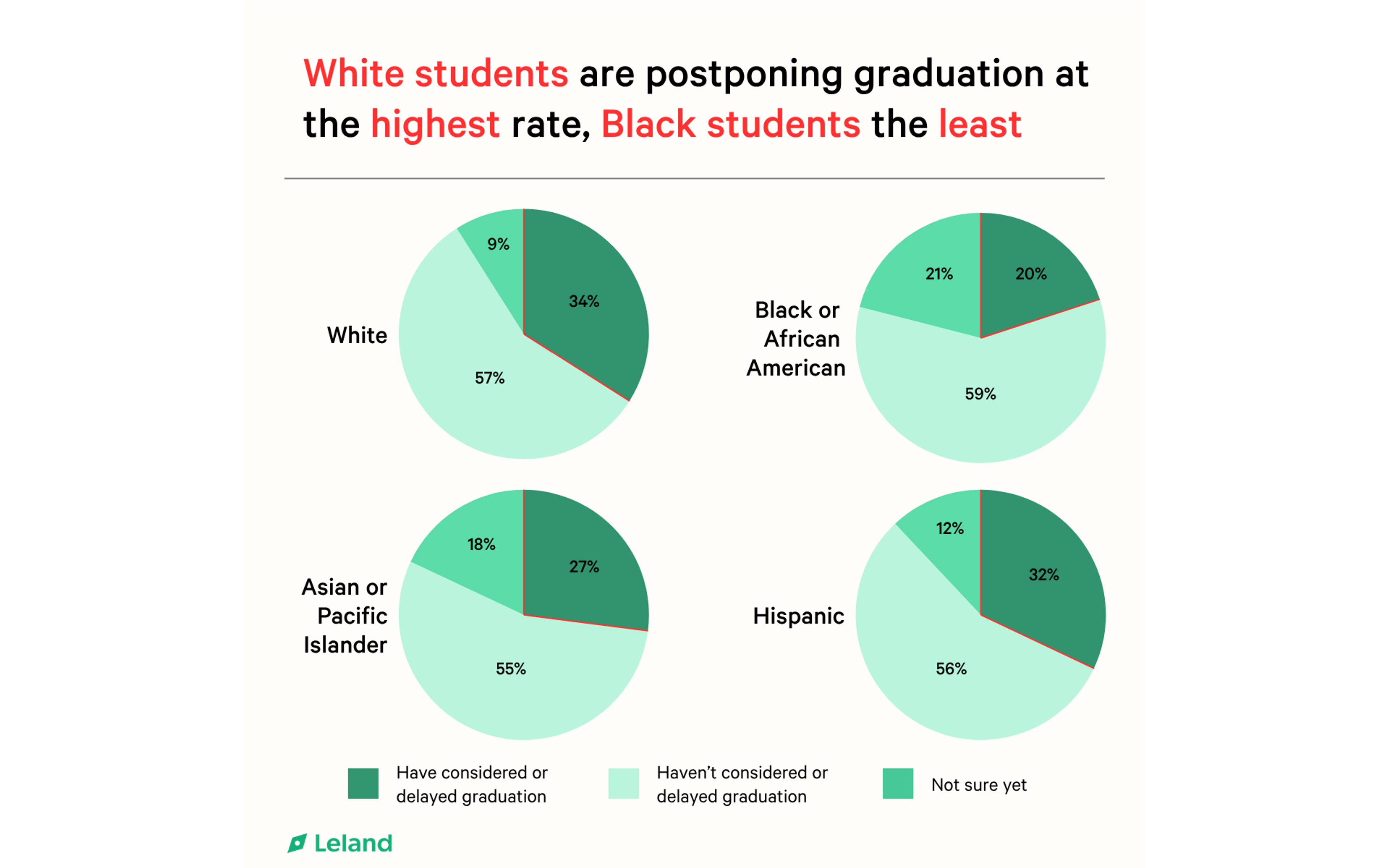

Race and ethnicity shape the story, too. White students report the highest rate of postponement (34%), while Black students are least likely to delay (20%). Hispanic and Asian students fall somewhere in the middle. These variations may reflect differences in financial flexibility, cultural expectations, or institutional support, but the net effect is the same: extra time, extra cost, and no guaranteed return.

When nearly a third of students see staying in school longer as their best career move, it signals more than individual choice. It points to a hiring system that is uncertain, and employment opportunities that are either limited or misaligned with demand. The result is that students are literally paying for more time to wait.

The Role of Universities: Are Career Centers Helping?

If career preparation is the unspoken second major for college students, then career centers are supposed to be their advisors. But according to students, these offices are falling short.

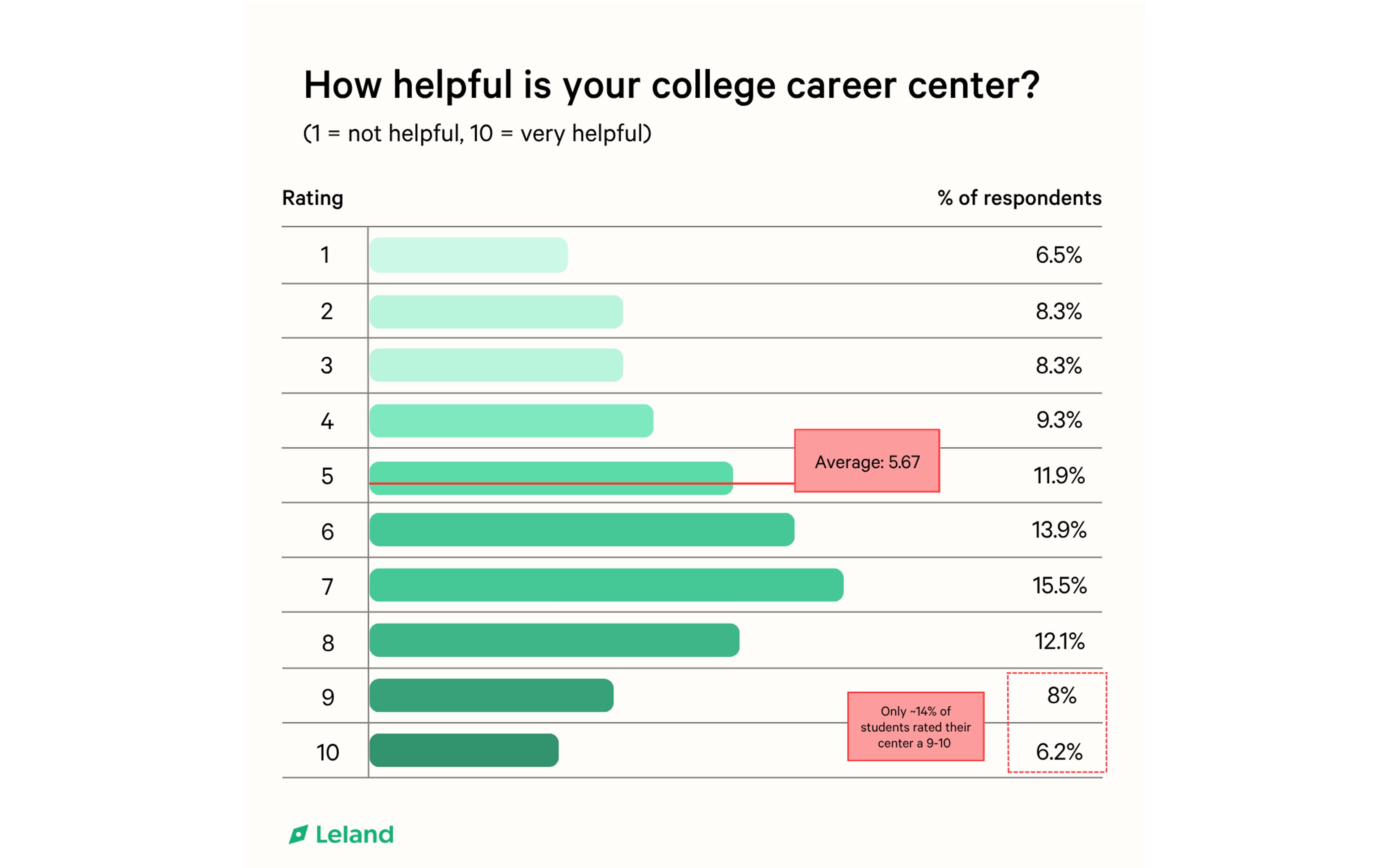

When asked to rate their career center’s helpfulness on a scale from 1 to 10, the average rating was just 5.67. That puts career services somewhere between “meh” and “mostly unhelpful.” In fact, fewer than 14% of students rated their center a 9 or 10. The most common rating? A tepid 7, followed closely by a shrugging 6 and an ambivalent 5.

Career centers are overwhelmed with demand, under-resourced, and unequipped to actually help students land jobs. The employment industry and demands of the market are evolving faster than ever before and companies like Handshake are supporting the "illusion of progress", with the career centers themselves doing very little to support the hiring of its students. Data from Inside Higher Ed supports these findings.

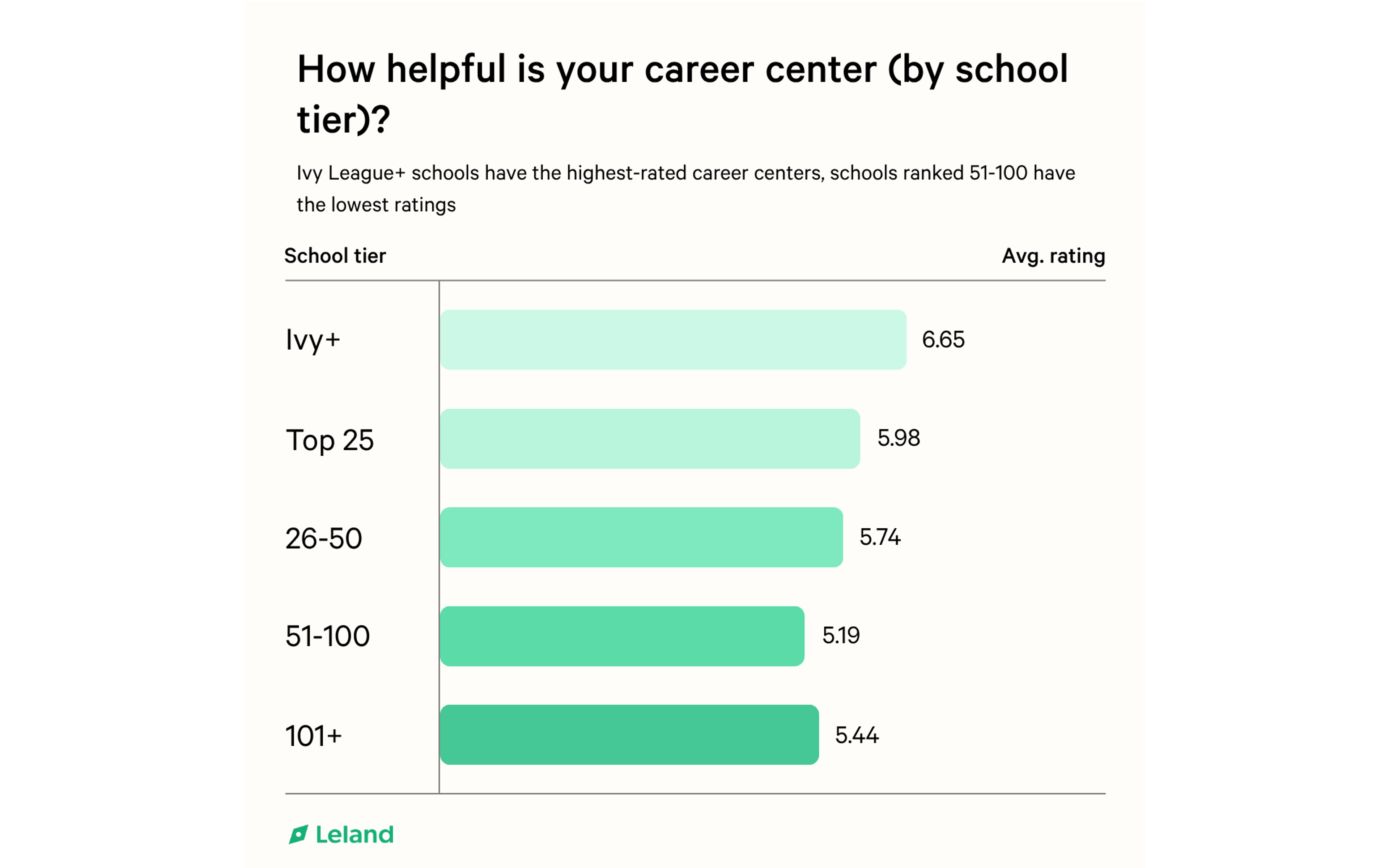

These aren’t isolated impressions, they’re systemic patterns. Students from lower-ranked schools consistently reported worse experiences. At Ivy+ institutions, the average career center rating was 6.65, but that number drops steadily as school ranking declines, hitting a low of 5.19 among students at schools ranked 51-100. Students at schools outside the top 100 fared slightly better (5.44), though still well below elite benchmarks. This is also likely affected by the brand name associated with top universities. Research from a non-profit, non-partisan arm of Harvard University found that students who attend these institutions are three times as likely to work at a prestigious firm and over two times as likely to get into an elite graduate school.

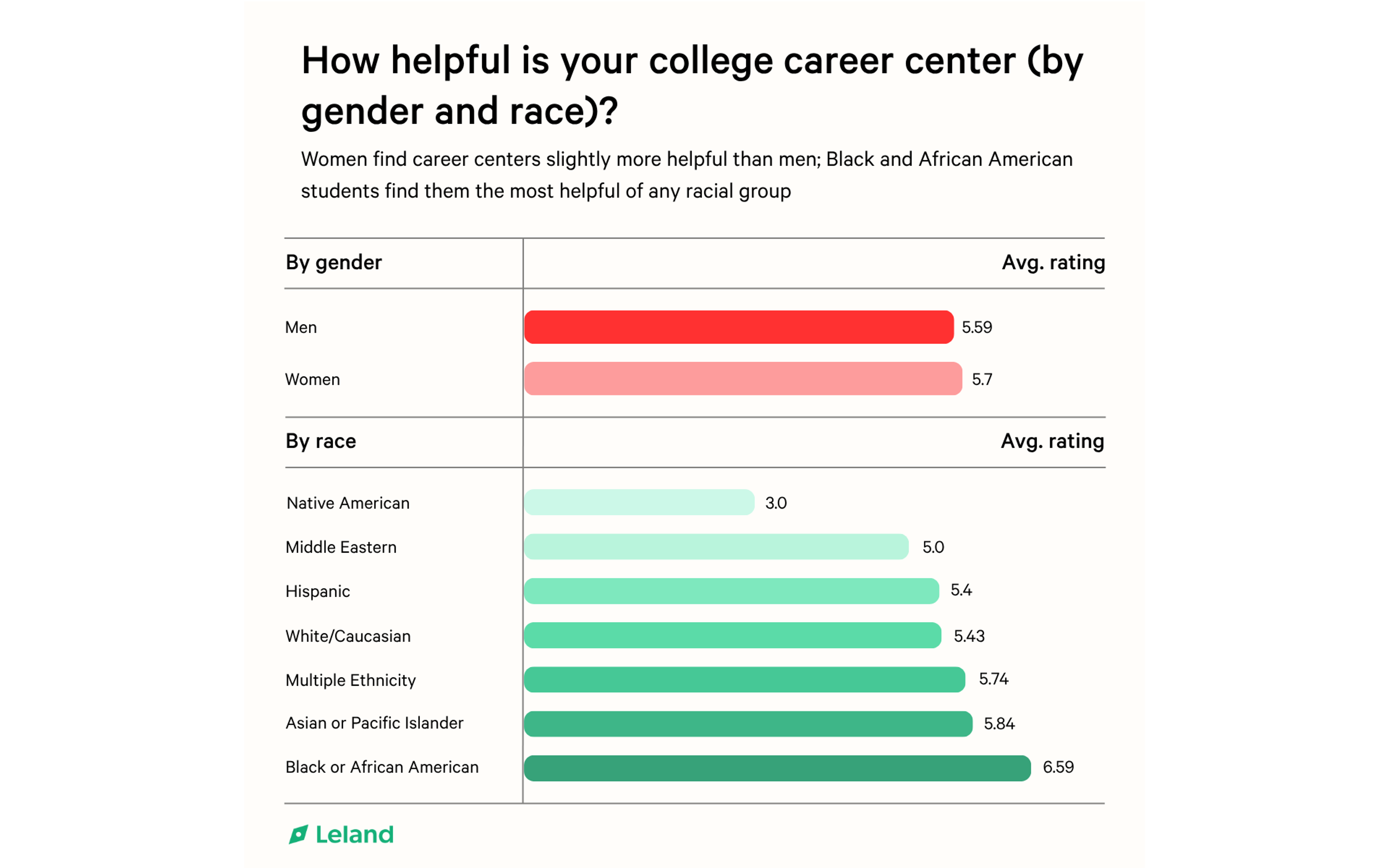

The gap widens when broken down by race. Black students rated their centers the highest – 6.59 on average – suggesting that targeted support programs may be making a difference. But Native American students reported the worst experiences, with a startling average of 3.0, followed by Middle Eastern students (5.0) and Hispanic students (5.4). White and Asian students hovered around the average, but even these ratings rarely exceeded “moderately helpful.”

Gender gaps also emerged. Women rated their career centers slightly more favorably than men (5.7 vs. 5.59), but the difference was marginal, and neither group found them particularly helpful.

For a generation drowning in unpaid work, ambiguous advice, and platform-driven recruiting, these numbers are more than disappointing; they’re a warning sign. As the cost of finding a job rises, students aren’t just asking for resume edits. They need coaching, context, and actual pipelines. And too often, they’re turning to TikTok or Reddit instead of the office meant to help them. In fact, one report found that over 41% of Gen Zers have made a career-related decision from advice on TikTok, highlighting the demand for information and resources that aren’t being found elsewhere.

The Systemic Gap Between Ambition and Access

At every turn, this data reveals the same truth: students are not just working hard, they're working alone. Across majors, demographics, and school tiers, the path to a first job is paved with unpaid labor, rising expenses, and institutional blind spots. The students with the time, money, or networks to navigate this hidden curriculum are pulling ahead – delaying graduation, spending more, and relying on brand names and networks to land roles. This is particularly concerning in an age of AI that favors well-compensated employees with high levels of training and skill, not entry-level positions.

The result is a hiring landscape that quietly but powerfully reinforces existing inequities. It’s not just that some students face longer odds, it’s that the system isn’t designed to level the playing field. When a career center’s usefulness depends on your ZIP code or school ranking, and when job prep can cost thousands before a paycheck even arrives, it’s clear the current model is failing.

Many of the students in this survey are doing everything right. They’re studying hard, applying widely, networking relentlessly. And yet they still feel like they’re falling behind because the process itself is misaligned with reality. Getting hired has become its own unpaid job. And unless we fix the system, the next generation of workers will burn out before they ever clock in.

This moment demands more than surface-level support. It calls for rethinking how we prepare students for life after college, not with platitudes or panels, but with real pipelines, real guidance, and real accountability. Until then, students will keep paying the price – in hours, dollars, and deferred dreams – for the first job they were promised their degree would secure.

Read More:

Browse hundreds of expert coaches

Leland coaches have helped thousands of people achieve their goals. A dedicated mentor can make all the difference.